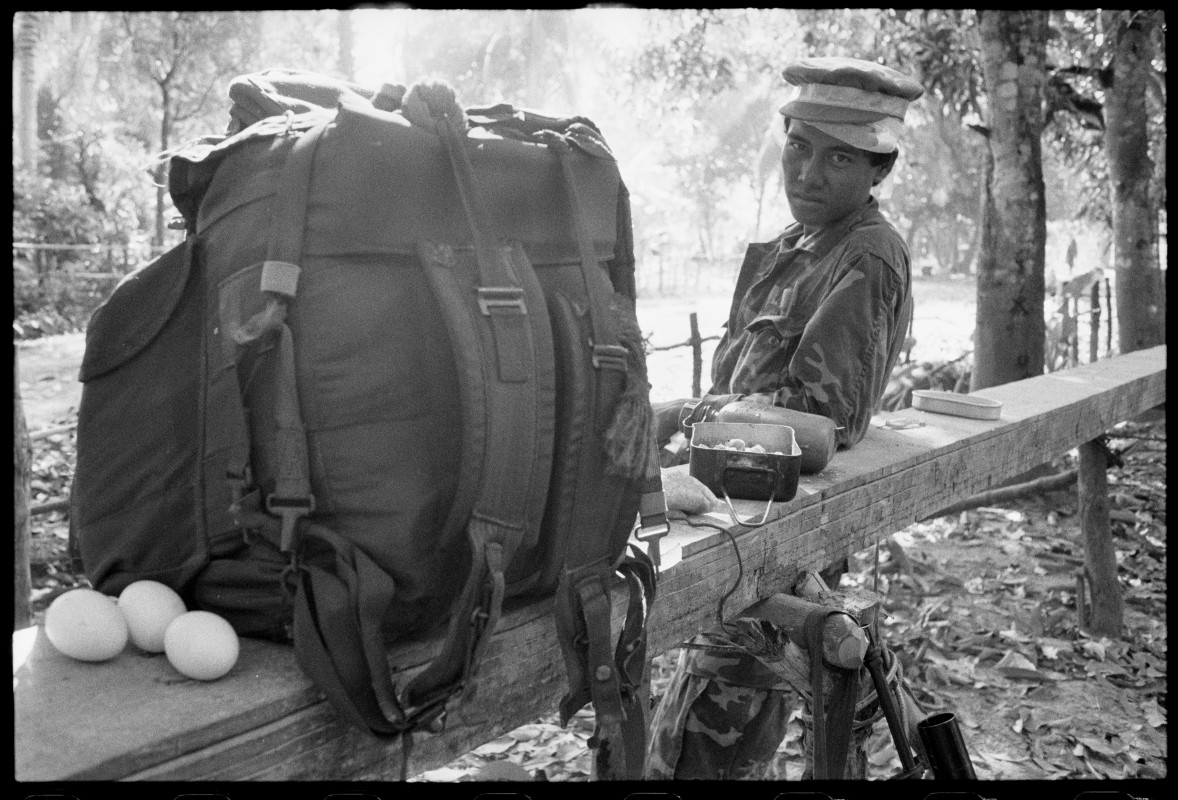

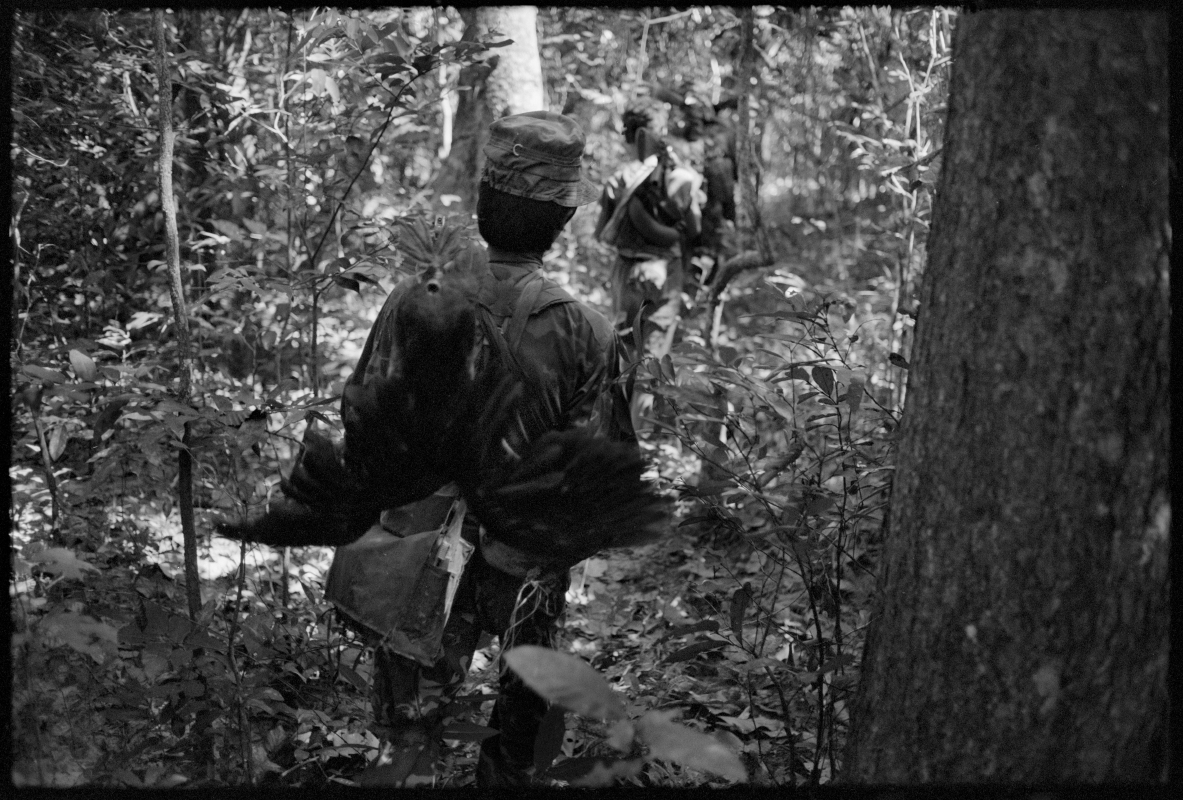

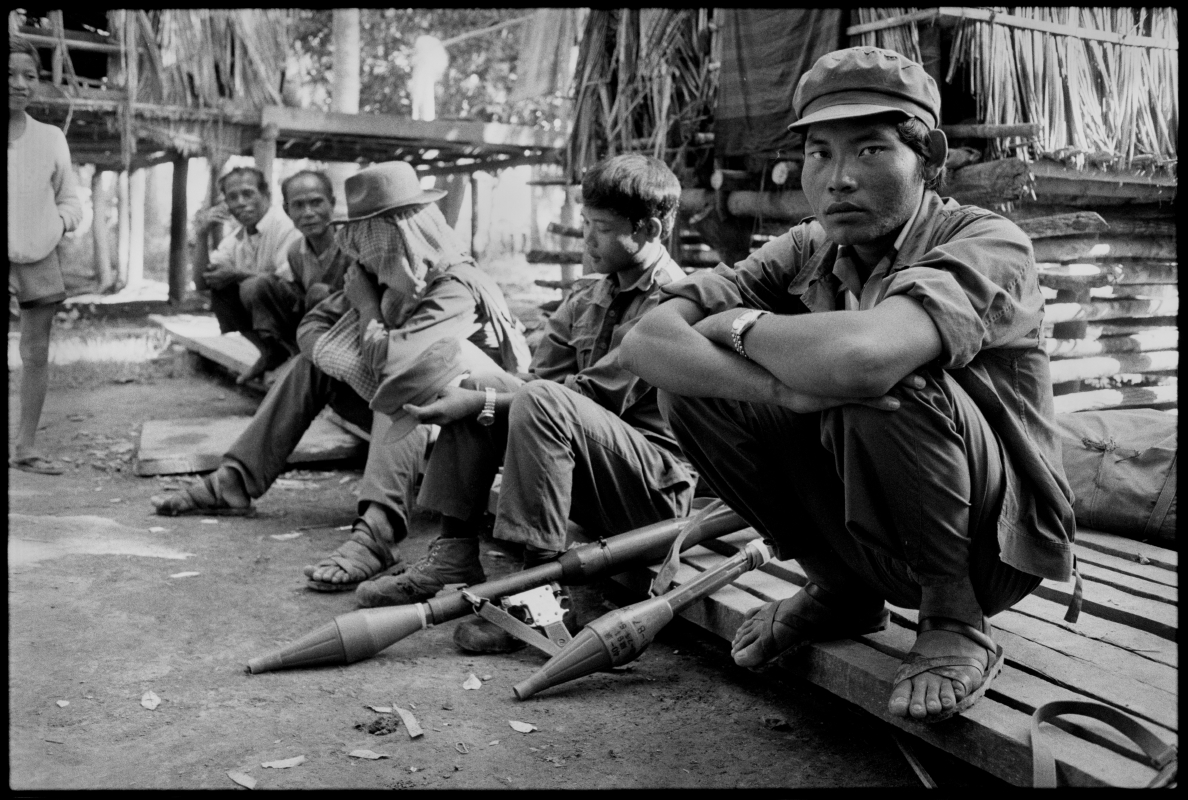

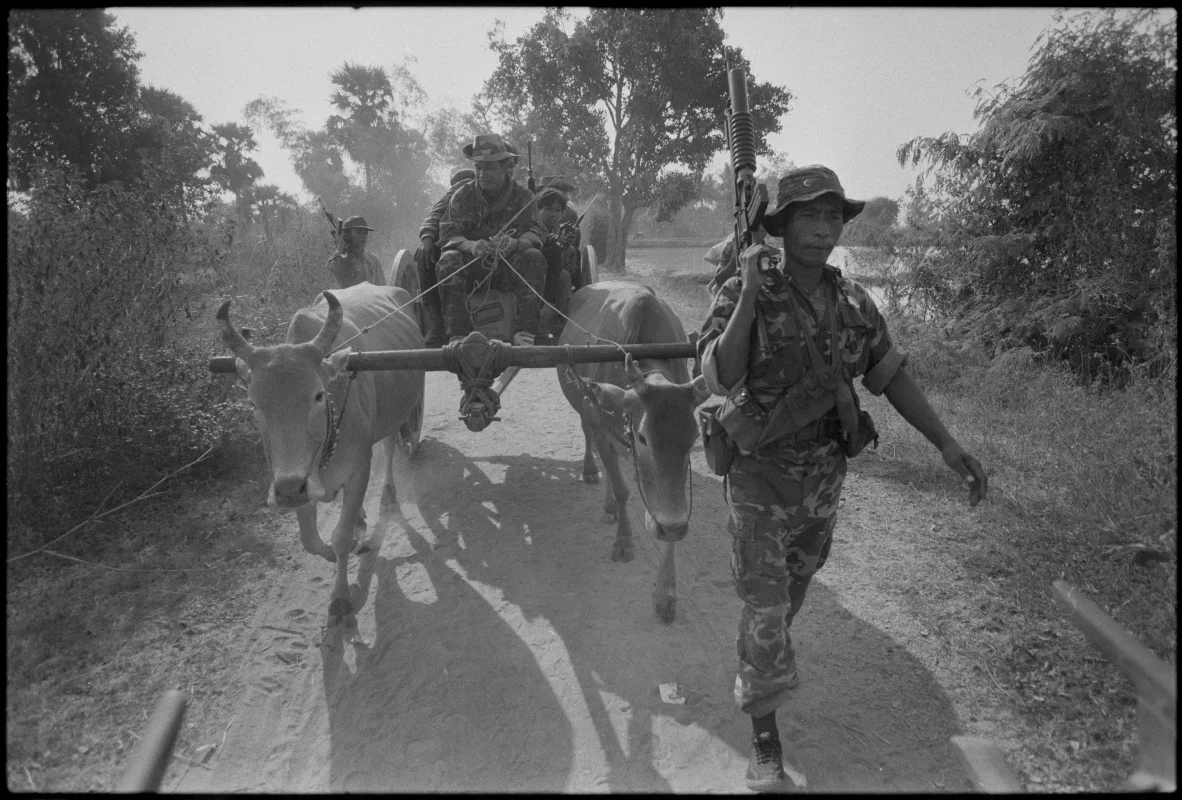

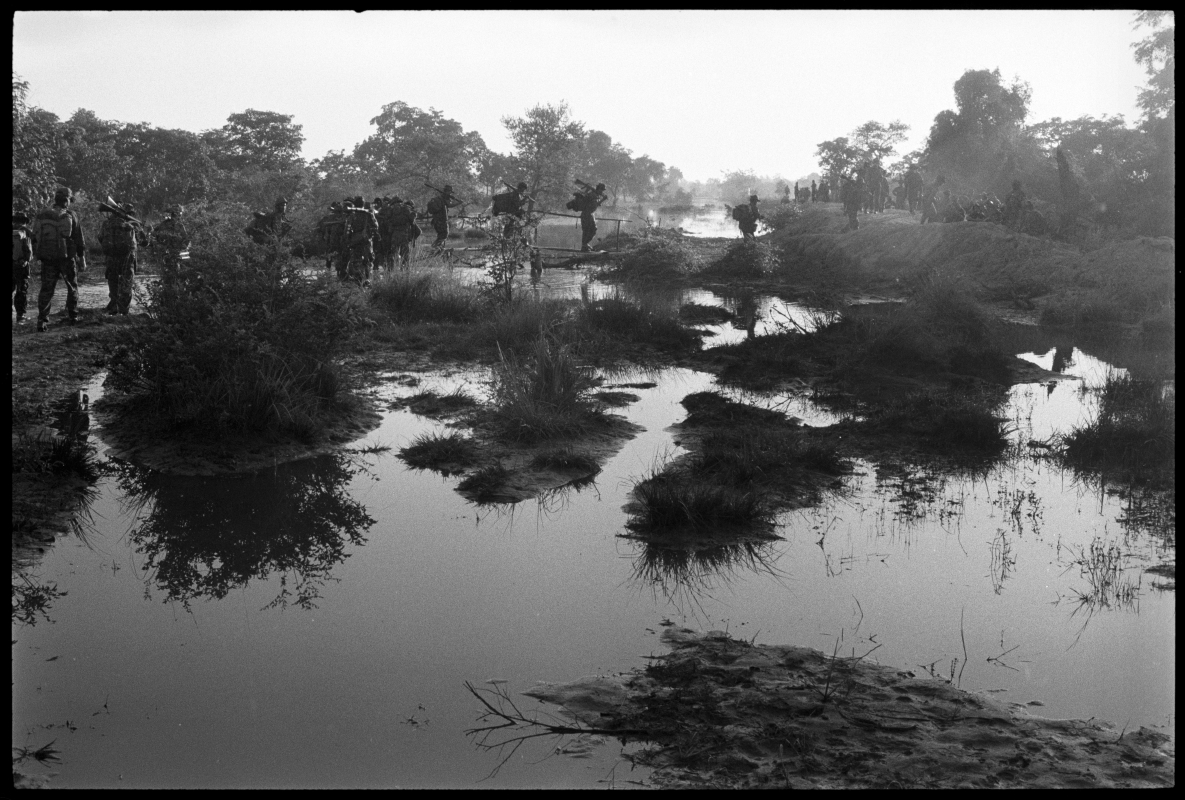

With Khmer guerrillas, Banteay Chmar. 1991. Photo © Philip Blenkinsop

My Journey To Southeast Asia

I left college after my first year because I knew what I wanted and it couldn’t be found in college. I wanted to go out into the world and tell stories, confront power, and wrangle with my own existential problems in a place where I would be a stranger.

I began my photography career in Indochina. The wars there had been present in my life when I was a child and young adult. I’d consumed the conflict in black and white on television and watched Brando and Sheen act it out in colour at my local cinema in Solihull in the middle of England. I was inspired by William Shawcross’s introduction to the book Tim Page’s Nam, describing Page’s journey from small town Kent to the Vietnam War. I had also worked for a brief time in community service with Vietnamese refugees in the village where I grew up and where I became fascinated by people different from anyone I had met in that small mono-culture. Indochina seemed to be as far away from home as I could go, and I desperately needed to go far from home.

In 1988, I flew to Bangkok on a cheap KLM flight and sat right at the back of the plane with all the smokers. I had a rucksack in the hold and my precious Billingham camera bag on my knees. It contained one camera (a used Canon AE1 Program), three lenses, and a tripod I would never use again. The flight was the third I had taken in my life. When it landed, I went to the Bangkok Youth Hostel on Phitsanulok Road and began a career as a photographer from a bunk bed in a dormitory.

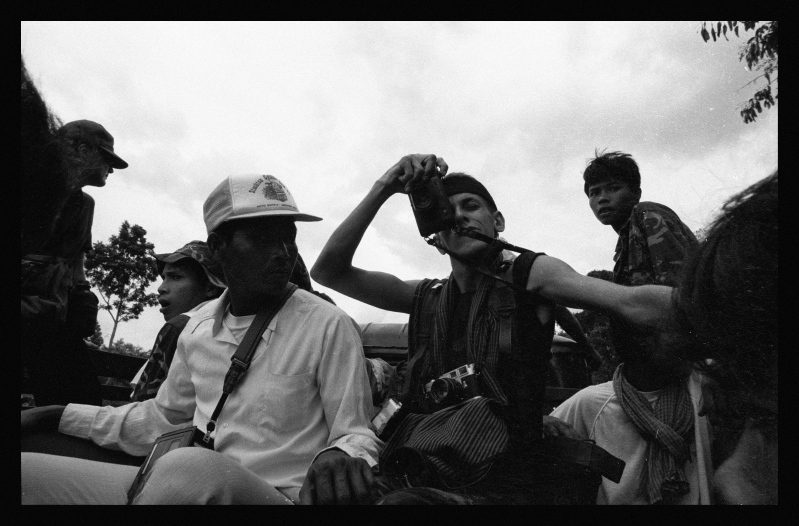

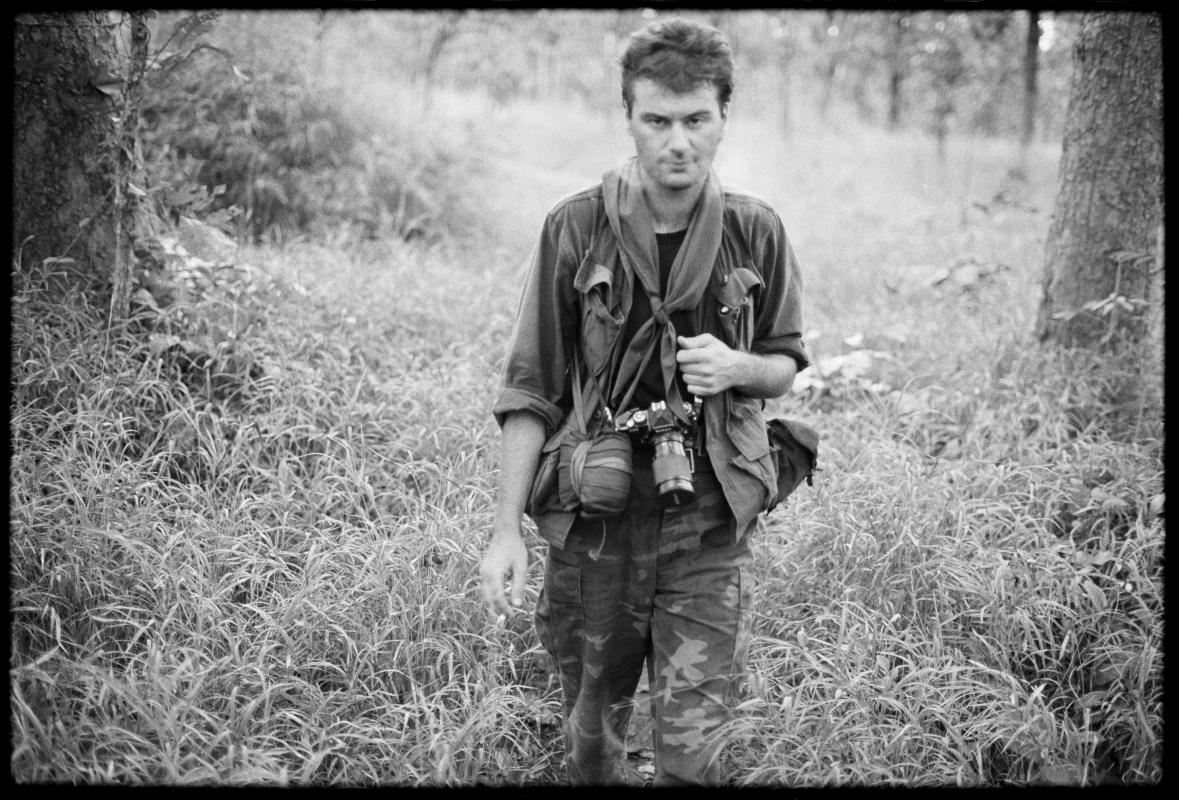

Some of the most important and enduring friendships I’ve ever made were formed at that time—with young men and women who were building careers just like I was trying to do. There were many stories to cover in the region, which was undergoing the trauma of the end of the Cold War, but a few of us decided to focus most of our effort on Cambodia. Philip Blenkinsop had recently arrived from Australia, Nate Thayer from the USA, Robert Birsel from the UK, and Thierry Falise from Belgium.

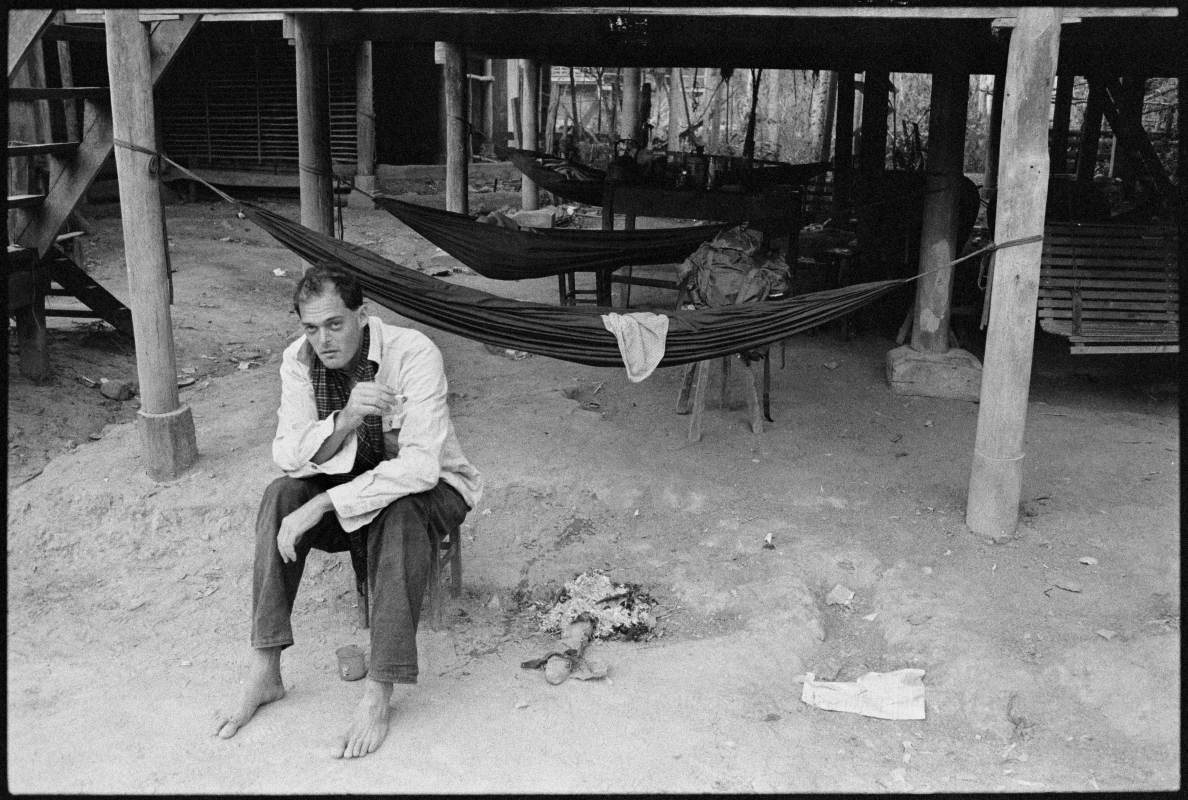

As I would be reminded many times later in my career, there was an omnipresent and painful personal conflict between my wonder over just being there and the distress I felt about the violence and injustice I was witnessing. Walking hand in hand through a minefield with a Khmer Rouge commander who was concerned for my safety but who 10 years earlier had been involved in the slaughter in Cambodia was painful and uncomfortable. Covering the conflict was simultaneously exciting, challenging, sordid, and repulsive. The magic of the environment and sense of marvel I had for the people that played host to it were sometimes overwhelming. In purely practical terms, the work was also inexpensive. Being poor with no commitments could be an advantage for us, because it meant we could spend weeks working without worrying about anything else. What we lacked in skill we could compensate for by being immersed for longer periods of time. I was so poor I would sell my blood to make money to eat, but I would not have swapped places with anyone.

I used to ride on the roof of an express bus from Bangkok to the Thai/Cambodia border. There I would photograph inside the UN refugee camps and make the connections I needed to photograph the dirty civil war inside Cambodia. A war nourished by Cold War superpowers far away. A war that saw former enemies—the Maoist Khmer Rouge, the KPNLF made up of former CIA stooges, and the royalist FUNCINPEC loyal to the deposed Prince Sihanouk—fighting together with funding from the USA and China to defeat Vietnam, which had never been forgiven for beating the USA, France, and China in the wars they’d fought the previous thirty years.

We would typically go into Cambodia with one of the guerrilla groups and run around trying to avoid the Vietnamese or Cambodian government forces. It was on these patrols or missions that I learned some great lessons in life, especially about my role as a journalist. I learned to mistrust everything I read, fight my own prejudice, and trust only what I saw—though not too much, as there were always factors at play that were impossible to account for. I also learned that freelance journalism was the only kind of journalism I wanted to practice. The liberty of being independent was essential to my life—and essential to being free to go where I wanted and to say what I felt needed to be said. I discovered, too, that I had an aptitude for being out on the edge and alone and afraid—three things I’d not previously been able to tolerate.

My commitment to the people of this region grew fast and has never diminished; it remains at the center of my life, and I continue to spend considerable amounts of time researching, photographing, and trying to understand what I see there. I will continue to post in later chapters more of my work from the region.

+ Reading List

The Customs of Cambodia. 1297. Chou Ta-Kuan

Four Faces. 1963. Han Suyin

A Dragon Apparent. 1984. Norman Lewis

The Sea Wall. 1986. Marguerite Duras

Brother Enemy: The War After the War. 1988. Nayan Chanda

Cambodian Folk Stories from the Gatiloke. 1989. Kong Chhean

River of Time. 1996. Jon Swain

When The War Was Over: Cambodia And The Khmer Rouge Revolution.1998. Elizabeth Becker

A Cambodian Prison Portrait. One Year in the Khmer Rouge's S-21. 1998. Vann Na

Survival in the Killing Fields. 2003. Haing Ngor

How Pol Pot Came to Power: Colonialism, Nationalism, and Communism in Cambodia, 1930–1975; Second Edition 2nd Edition. 2004. Ben Kieran

The Gate. 2004. Francois Bizot

Pol Pot’s Little Red Book: The Sayings of Angkar. 2005. Henry Locard.

The Lost Executioner. 2006. Nic Dunlop

Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare. 2006. Philip Short

Building Cambodia: 'New Khmer Architecture' 1953-1970. 2006. Helen Grant Ross & Darryl Leon Collins

A History of Cambodia, 4th Edition. 2007. David Chandler

The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, Third Edition. 2008. Ben Kiernan.

Phnom Penh: A Cultural History. 2008. Milton Osborne

Satellite Remote Sensing for Archaeology 1st Edition. 2009. Sarah H. Parcak

Bophana. 2010. Elizabeth Becker